Until the 1980s, independent transport operators in Peru, who were primarily from the nation’s lower income groups, had a negative public image. Almost all proposals seeking to regulate public transportation sought to eliminate them. The presiding theory was that the poor could not become entrepreneurs and only government could (or should) run public transport. In November 1986, however, the publication of De Soto’s book The Other Path, based on years of ILD field work and analysis, revealed a different picture: 85 percent of Lima’s urban transportation belonged to extralegal entrepreneurs and the total replacement value of their fleet was US$ 620 million. Most of Lima was literally travelling through the city in extralegal vehicles. The ILD’s analysis also revealed that for decades government had put in place numerous legal obstacles impeding private lower income entrepreneurs from gaining direct legal access to the urban transportation market.

The ILD’s findings had a positive impact on the transport operators. In December 1986, backed by 120 grassroots organizations across the nation, the drivers published a communiqué titled “The Path of 300,000 Drivers,” requesting the ILD’s help in finding a comprehensive solution to the transport problem. “We are burdened with a legal system that persecutes and thwarts popular initiative,” the drivers wrote, “while discouraging formalization and encouraging the politicization of the service.” The transport operators had begun to see themselves not as the proletariat but as entrepreneurs.

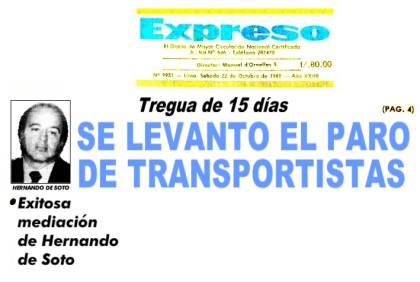

The Government, however, failed to react. Finally, in October 1988, the National Front for the Defense of Transportation declared a nation-wide strike that paralyzed economic activity throughout the country and threatened to undermine political stability in the middle of the government’s all out war on terrorism. Three days into the strike, the ILD decided to intervene as mediator in the conflict. Grateful that the ILD had demonstrated to the country that they were indeed entrepreneurs, the drivers temporarily called off the strike.

Meantime, the ILD formed a mediating commission with representatives of several professional associations to evaluate the transport sector. After a thorough analysis, the commission submitted a report to the parties involved and went public with it. The transport operators felt vindicated, that solutions were on the way, and therefore ended their strike. Though the ILD’s legal proposal was never adopted, the authorities drew from its work and eventually enacted several laws to reform transportation legislation, recognize the needs of transport owners and workers, and reduce unnecessary costs. In recognition of its successful solution to what was considered one of Peru’s most dangerous labor strikes, the National Association of Industrial Relations Managers awarded the ILD its “Labor Peace Prize.”