In an exclusive interview the night before his election as President of Peru on June 10 1990, Alberto Fujimori identified his constituency: “The truly marginalized Peruvians are the informal people, that large sector of the population that Hernando de Soto studied in his book The Other Path, which I read some time ago. It was then that I realized that it is they who are the great new Peru.” In fact, just 22 days earlier, Fujimori had published his government program 50 percent of which was based on ILD proposals for reform.

The day after his election, Fujimori offered De Soto the post of Prime Minister. He also requested that the ILD founder help him carry out his political program with particular emphasis on stemming Peru’s raging 2000 percent annual inflation rate and reinserting the Peruvian economy into the international financial system. De Soto was eager to take on the challenge but without losing his independence; therefore, he declined the Prime Minister’s post but agreed to be the President-elect’s principal advisor and personal representative abroad.

On the third day after his election, Fujimori, together with some of his early campaign advisors and De Soto, met with Martin Hardy, a representative of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Fujimori’s presidential campaign had been based on the promise of “no shocks” to the economy, and he made his position clear to Hardy by assuring the IMF’s man that he would do “nothing that will affect the purchasing power of Peruvians.” In other words, Fujimori had made it clear that he would not stabilize the economy in one fell swoop.

As soon as the meeting with the IMF was over and in the presence of others, De Soto assured Fujimori that there was no other way to stop Peru’s spiraling inflation without a shock. He suggested that the President-elect change his mind and entertain an alternative that the ILD would draw up for him. De Soto also proposed that for Fujimori to make a reasonable and informed decision, he should meet with the leaders of the world’s most important international organizations in order to get their honest appraisal of Peru’s economic options. Fujimori agreed, and this is how events unfolded over the next two weeks:

-

De Soto, through his brother Alvaro, an Assistant Secretary General of the United Nations, arranged for UN Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, also a Peruvian, to host a meeting at U.N. headquarters in New York where the President-elect could assess his options for Peru’s economic future with the director of the IMF, Michel Camdessus. The presidents of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) would also be present at the meeting.

-

With Fujimori’s consent, De Soto invited the Peruvian banker Carlos Rodríguez Pastor, who had also served as Minister of the Treasury but was then residing in San Francisco, to prepare a memorandum describing a shock stabilization program that could be weighed against the gradualist program that Fujimori had preferred up to then. De Soto and Rodríguez Pastor also prepared a list of economists and technicians to provide support should the President decided to choose the ILD’s option.

-

Before the New York meeting, De Soto, in his role as Fujimori’s representative, met with IMF Director Camdessus and informed him that the Peruvian President was prepared to do what was necessary to repair the nation’s economy. All Fujimori wanted from the IMF, De Soto assured Camdessus, was an unambiguous signal as to what path Peru ought to follow. Would the IMF director be willing to talk straight? Camdessus assured De Soto that he would not couch his reply in diplomatic language but would tell Fujimori what he saw as his only reasonable alternative. De Soto conveyed that message to the American and Japanese authorities, who, given the brief time left before Fujimori took office, also agreed to be candid with the Peruvian leader.

On June 29, 1990, the summit meeting took place on the 38th floor of the U.N. headquarters in New York City. The meeting was hosted by Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, and attended by Fujimori, Camdessus, Barber Conable, President of the World Bank, and Enrique Iglesias, President of the Inter-American Development Bank, and De Soto. When President Fujimori presented his no-shock, gradualist approach for economic reform in Peru, the room was filled with an eloquent silence. The world’s premier international financial authorities were clearly not in favor of the President-elect’s no-shock preference. Following the presentation of the alternative —the ILD’s shock proposal— the Director of the IMF declared: “This is celestial music to my ears.”

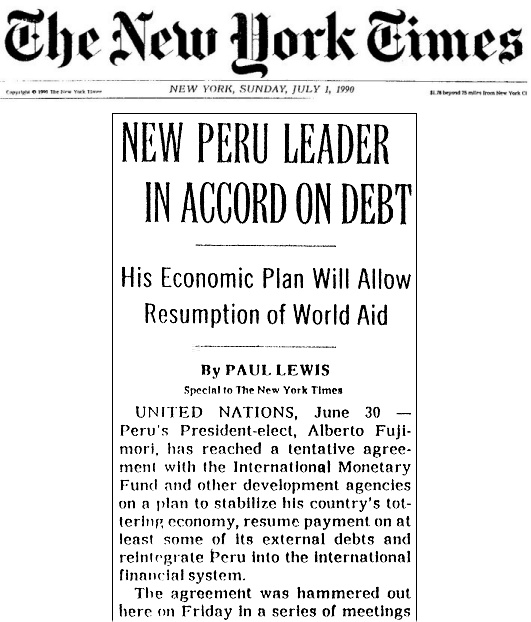

The response at the UN meeting immediately wiped out any doubts Fujimori may have had, and he decided there and then the course the country would take during his administration. This he confirmed to the New York Times the next day. And thus on July 1, a front page headline in the Times reported Fujimori’s general agreement with the IMF to stabilize Peru’s economy, pay at least some of the country’s outstanding debts, and reintegrate Peru into the international financial system.

Four days later, on July 5, in a meeting in a Miami hotel organized by the ILD, Fujimori began interviewing the candidates to carry out the stabilization program, some of whom were eventually hired. But the ILD failed to find a candidate to fill the important post of Minister of Finance and Economy —the person who would have to announce ‘the shock’ to the country and then carry out the stabilization program. It was, at the time, perceived as a daunting political task, and several candidates turned the post down. Other possible candidates for the job did not satisfy Fujimori’s requirements. It was only later, back in Lima, after many more interviews that it became clear that the only acceptable candidate for Fujimori, who also was willing to announce the hard news of the forthcoming economic shock, was Juan Carlos Hurtado Miller, notorious for his opposition to free markets. Fujimorinamed him his first Minister of Finance and Economy.

In the meantime, since it was clear that Fujimori wanted a Finance Minister committed to his new policy, the ILD hired one of the candidates who had originally refused the position but was advocate of economic shock, Carlos Boloña, then residing in the United States. That put Boloña in line to replace Hurtado, whom Fujimori finally pushed out after five months, in February 1991.

And thus the ILD’s years of analysis of the Peruvian situation and its unequivocal stance in defense of the poor, allowed it to seize the moment and help Peru make the right decision at the right time.