After years of research, the ILD began to understand that in Peru democracy had essentially been reduced to the act of voting. Because voters have no mechanisms at their disposal to register their reaction to new laws or policies, and the authorities do not have peaceful and organized means to gather public opinion or to channel existing initiatives by citizens, political participation ends at the ballot box. Peruvians thus hand over a virtual “blank check” to their elected officials, who, in turn, convert this check into thousands of laws and decisions that significantly affect the life of the people —without consulting or being accountable to them. And so, even when politicians govern with the best interests of the electorate in mind, they do so in ignorance and on the basis of biased information provided by those with special access to power.

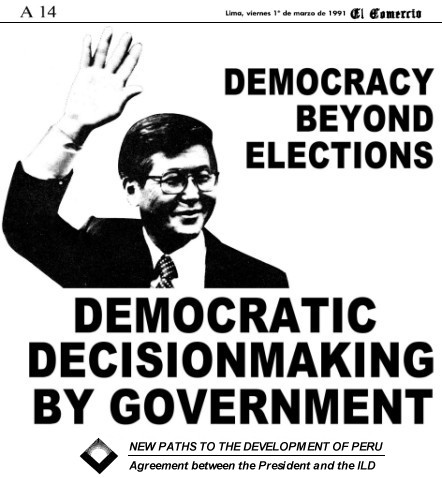

On February 26, 1991, President Fujimori, in a nationwide televised address, subscribed the ILD diagnosis of Peruvian democracy and announced that he was enacting the Law for Democratic Decision-Making by Government that had been drafted for him by the ILD. He told his audience that for the first time in history Peruvians would have the following rights: to know the contents of laws before the Executive Branch or its agencies enacted them; to express their opinions by submitting their comments or by participating in public hearings when laws were being formulated; to identify public officials drafting laws and hold them accountable. In addition, citizens and the media would have, among other things, the right to have access to government controlled information; challenge arbitrary laws quickly via clearly defined procedures; consider requests as resolved in their favor if they had not been addressed within the time allotted by law; have the right to initiate referendums and participate in government advisory committees.

In March 1991, President Fujimori, under pressure from his own ministers and the nation’s mercantilist sectors, enacted a law that had been watered down significantly. Caretas, Peru’s leading newsmagazine, summarized the episode in this way: “The ILD’s project was the object of a mass attack from all fronts.” The opponents of the law were, Caretas pointed out, “those whose interests are affected by the pre-publication of laws. Namely, those who have access to government through political influence, power, bribery or kinship. [Not to mention] the very people who hold the power to make laws, which includes ministers, directors...”

In spite of this political setback to the ILD’s reform efforts, the consensus among the people concerning the ILD proposals remained favorable. Surveys indicated that 81% of the population supported the proposals to democratize government decision-making. In view of such overwhelming popular support, the ILD decided to wait for a new window of opportunity. As it turned out, President Fujimori himself opened that window less than two years later.