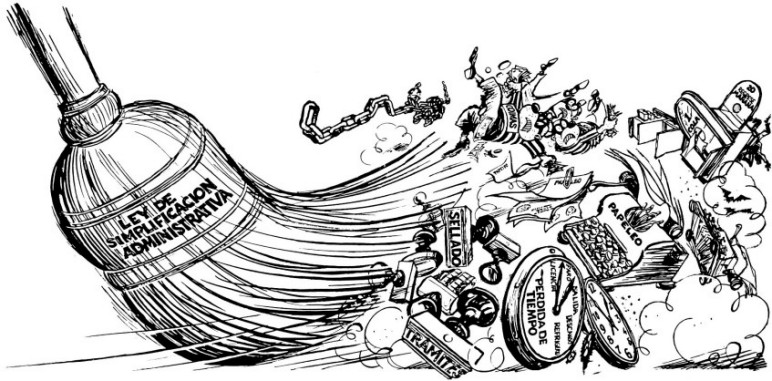

To deal with the queues, paperwork and excessive bureaucratic procedures that caused most Peruvians so much lost time, unnecessary expense, not to mention the general constraints on economic activity, the ILD created a draft of the law and an administrative strategy to streamline bureaucratic procedures and facilitate institutional reform.

This proposal was based on public hearings and debates throughout the country, featuring legal specialists and congressmen. Such events, which went on for two years, not only added substance to the ILD proposal but created an enormous wave of support for it.

As a result, in June 1989, the ILD’s draft was unanimously approved in Congress by all political parties and, with no major modifications, became Law No. 25035 for Administrative Simplification. Government now had the mandate and means needed to decrease or eliminate unnecessary red tape, streamline public administration, and substantially reduce transaction costs. The new law rested on four pillars: 1) substituting most ex ante requirements that create legal bottlenecks with ex post controls; 2) keeping the costs of operating legally below those of operating illegally; 3) decentralizing decision-making procedure; 4) promoting user participation to control the application of all decisions.

Shortly after the law was enacted, President Alan García Pérez called upon the ILD to manage the implementation of the simplification process. The ILD signed an agreement with the Government in July 1989. The ILD proceeded to design a unique mechanism called “The Administrative Simplification Tribunal” to gather and evaluate proposals from citizens for deregulation and to check up on how various bureaucracies were responding to the dictates of the law. To facilitate public participation, bright yellow boxes were placed in the ILD headquarters, in several government offices as well as at all the radio, television, and newspaper outlets to make it as convenient as possible for people to deposit their grievances. The media were encouraged to review the grievances they received, and when they saw an astonishing or outrageous story, they took up the cause, creating the kind of public pressure that politicians found impossible to ignore. The complaints were dealt with in a publicly televised tribunal managed by the ILD and presided over by the President of the Republic every second Saturday morning. The televised proceedings racked up ratings that any entertainment series would have been proud of.

Over the year the Tribunal was in operation —with the President, by law, in attendance— more than 200 bureaucratic knots were untied. The time previously required to fulfill hundreds of different kinds of official procedures, including obtaining a passport, applying to university, and getting a marriage license, was cut across the board at least 75 percent. To get a marriage license, which used to take 720 hours of bureaucratic hassles, was reduced to 120 hours —thus helping women secure their rights as marriage partners. The number of documents required to apply to university was reduced from nine to two. At the end of President Garcia’s term in July 1990, 79 percent of the population (and 84 percent of the poorest among them) rated the Law of Administrative Simplification as the best law enacted during the 1985-1990 legislative period.

After the change of government in July 1990, the ILD presented President Fujimori with a package containing 39 draft laws for legal reform derived from the ILD’s analysis of the grievances received by the Tribunal and based on the principles of administrative simplification. The Executive branch eventually enacted 15 of these, including the Unified Business Registry for incorporating small businesses, the liberalization of the land real estate markets, and a pardon for prisoners whose cases had never come to trial.

The Fujimori Government used the instruments contained in the Law of Administrative Simplification to carry out most of the structural adjustment reforms that were required to insert Peru into the global economy. Unfortunately, the President refused to continue the televised tribunal perceiving them as a remnant of the government of a political foe whose popularity ratings had soared within a few months from six to 25 percent, thanks mainly to the exposure he received from his appearances at the tribunal.