In 1984, to further increase the odds that the real needs of the people would be heard by the government, the ILD mounted a campaign for an independent national “ombudsman” to represent the interests of citizens, no matter how poor they might be. Though there was no provision in the constitution for such a position, it authorized the Attorney General to “defend the public interest.” The ILD petitioned the sitting Attorney General who agreed that he, too, thought that an ombudsman would improve the quality of Peruvian lawmaking. In July 1984 and December 1985, the ILD signed two agreements with the Office of the Attorney General to design the legal mechanisms for Peru’s first “Office of the Ombudsman” —El Defensor del Pueblo.

In February 1986, the ILD launched the first ombudsman project. A special team from the institute set up several offices in downtown Lima to receive and process grievances. During the first month, more than 153 grievances representing 300,000 individuals were received either in person or by mail. More than half of the complaints were about the difficulties of gaining legal access to housing. The ILD’s agenda was now clear: It had to learn why housing had become such a primary concern for so many Peruvians. What precisely did it take, or cost, for an ordinary family to get a piece of real estate?

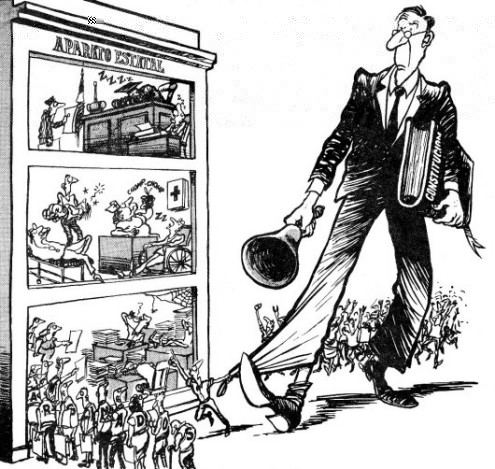

Using real case histories and simulations, ILD researchers discovered that existing government procedures to allot undeveloped land involved 207 bureaucratic steps that could take upwards of 3 years to complete; gaining a legal property title might take as long as 20 years! Suddenly, the reason became quite clear for the number of housing complaints —and why there had been 282 violent land invasions in Peru in 1985 alone. The majority of Peruvians did not have legal access to land, leaving them no alternative but to squat on private and public lands.

ILD proceeded to draft eight proposals for reforming the legal property system and addressing other bureaucratic hurdles that alienated the poor from the law, including the formalization of property, access to public information, administrative simplification, and arbitration, which it turned over to the Office of the Ombudsman. Once again, however, when faced with a concrete proposal, the government resisted change. A new Attorney General had also taken office, and since the Attorney General was then part of the executive branch, he was pressured to drop the proposed reforms. The ombudsman was in place but politically stymied. The ILD was then forced to discontinue its relationship with the Attorney General.

But, once again, a failure had its silver linings: Poor people had tasted the benefits of having government listening to them directly, and the Government would be hard-pressed to persuade them otherwise; for the ILD’s part, it had discovered beyond a doubt that property was an important issue for most of the people of Peru, demanding further study. In addition, the ILD’s hard work of setting the ombudsman concept into motion turned out not to be in vain: Peru’s New Constitution of 1993 incorporated the Office of the Ombudsman —as an autonomous entity no longer part of the Attorney General’s office, just as the ILD had originally proposed and kept pushing for until that very date.